Despite being an incredibly common way for families to preserve and pass down their wealth, trusts are often experienced by those involved as overly complicated, difficult to manage, and confusing. Due to a lack of understanding, trusts can lead to family conflict around succession, governance, and inheritance. These issues can impact not only the functionality of the trust and the management of assets, but they can also have a great impact on family relationships.

In simple legal terms, trusts are fiduciary arrangements that allow a third party, known as a trustee, to hold assets on behalf of a single beneficiary or multiple beneficiaries. In many family businesses, trusts allow for protection between the family assets and any risks to these assets. Families may place ownership of their business operations or real estate holdings into a trust to protect these assets from lawsuits, creditors, or taxes and to minimize estate transfer taxes across generations.

Upon placing assets in a trust, families will immediately experience a shift in the roles and responsibilities within the family business. Decisions are no longer dependent on who has what ownership percentage, as the ownership is now held in trust. This makes the trustee-beneficiary relationship far more important than who owns how many shares.

Ultimately, the success of a family trust is built on the understanding of how it functions and the purpose it serves. In this two-part article series, we will explore the topic of family trusts through the example of the Smith Family Enterprise Group. By following this multi-generational family from its origin as a small, single-product farm in California to a large-scale family enterprise with multiple operating businesses, we will cover the questions that all families should ask themselves when establishing a trust, as well as the questions that should be asked during a transitionary period of the trust, such as the succession of the trustee.

Setting the Stage

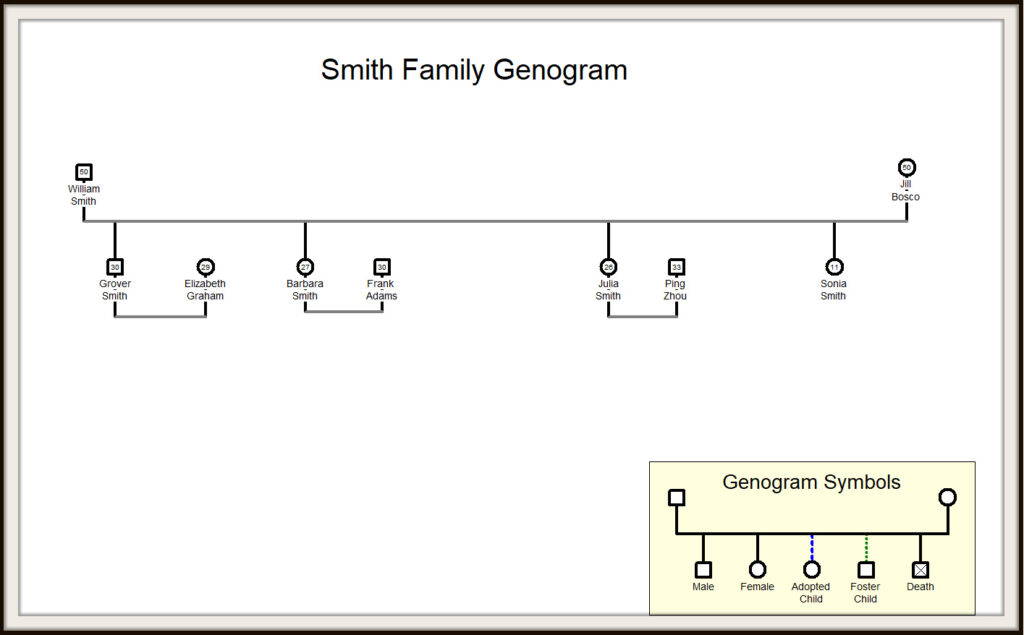

Following the events of the Dust Bowl, Bruce and Becky Smith purchased a 50-acre farm in central California in 1926. They gradually grew it to 150 acres, while raising their son, William, on the farm. William married his high school sweetheart, Jill, when he was nineteen years old and then took over the farm from his parents when he was thirty. William and Jill had four children, with an eighteen-year age difference between the oldest and youngest.

While his children grew up, William was the head of the family business and called all the shots. Since he was an only child, there was never any question about who would take over the leadership role from his father. However, with four children of his own, William had growing concerns about the succession of the family farm. The last thing he wanted was to create conflict between his children. William also wanted to ensure his children retained as much wealth as possible after his death. Upon voicing his fiscal concerns to his financial advisor in the early 1980s, William was counseled to put the farmland into an irrevocable, generation-skipping trust and to make one of his children the trustee and his other children beneficiaries.

Let’s now dive into the who, what, where, why, and how of the Smith family trust, starting with the why.

The Why

The reason why a family first establishes a trust can be multilayered, often having both financial and emotional reasons. For William, the emotional “why” was his desire for family harmony. He didn’t want the family business to come between the family, so placing the land in a trust allowed the ownership to be separated from the family members, thus reducing the likelihood of ownership conflict.

William’s decision to place his family’s farmland in trust came not only from what he wanted, but also from what his children wanted. Of William’s four children, his eldest son, Grover, was the only one who showed a real interest in the business and would have been the logical choice for leadership. However, William was not comfortable passing ownership to Grover alone. Grover also expressed that he did not want to “run” the farm and the business with his sisters and their husbands. William wanted to ensure that he treated his children fairly and understood Grover’s concerns about being his sisters’ and brother-in-law’s “boss.”

In this situation, from a family-relationship perspective, putting the land in a trust was the optimal solution for these dynamics. The trust ensured that all his children would have equal monetary rights and that no single person would be able to sell their portion of the land. Additionally, the trust structure allowed William’s grandchildren the opportunity to become involved in the business if they ever wanted to.

In addition to the context-specific emotional reasons that can lead to families creating a trust, other tangible advantages come from placing assets into trust, including protecting those assets from lawsuits, tax planning purposes, creating equality between beneficiaries, protecting a beneficiary who may have mental or physical conditions that prevent him/her from direct ownership, and generational preparedness. Ultimately, a family’s “why” in creating their trust will be a reflection of their situation and circumstances.

The Who

When a grantor, the person establishing the trust, first creates it, there are two roles that they must designate people to fill: the trustee and the beneficiary (or beneficiaries). The trustee is the person who will be responsible for managing the assets held within the trust, making distributions per the terms of the trust, and handling the financial management, legalities, and accounting administration of the trust. There can be more than one trustee. The beneficiary, or beneficiaries, receive the benefits of the assets. There is often more than one beneficiary currently alive and future beneficiaries who are yet to be born.

When families designate their first trustee(s), they must consider the skills necessary to be good stewards of the trust as well as the relationship with the beneficiaries. William wanted to name Grover the trustee because it felt safe. William had confidence that Grover would be making decisions that would benefit the farm and the family. For this reason, many families choose a family member as the first trustee since they are “known” to the beneficiaries. In the 1980s, when creating an irrevocable trust this became more complicated due to the rules around “control” of assets.

Because William was creating an irrevocable trust picking a trustee becomes more complicated. William was advised to have someone other than Grover be the trustee to preserve the tax planning benefits of the trust. The lawyers told William, the grantor, to make Beth, a junior lawyer in the firm he uses, the first trustee, and his children and grandchildren the beneficiaries. William chose Beth because he was told none of the children could be trustees and beneficiaries at the same time. This bothered William, but Beth assured Willam that she would take her direction from Grover. Beth said she is not a farmer, and that she would be a trustee who just checked the legal requirements. Additionally, she sits on the library board with Grover and had attended high school with one of William’s daughters.

The beneficiaries themselves also have responsibilities to the trust. Beneficiaries must understand the assets that are held in the trust and maintain open communication with their trustee to ensure that their needs are met, and their opinions heard. Beneficiaries should not be blind recipients of distributions but rather active participants in the trust who work with the trustee. When first establishing a trust, the people filling the roles of trustee and beneficiary must understand their positions and the responsibilities they entail.

The What

It’s up to the grantor which assets are initially placed in the trust. Depending on the type of assets held within the trust, certain elements must be considered when thinking about business ownership in terms of operations, voting rights, and governance. The “what,” or assets, going into the trust are directly linked to the structure of the trust that is created.

When William established his family’s trust, he placed all the farmland inside of it, including the homestead house and the barns. The land is often placed in trust because it protects it from lawsuits and future generational estate taxes. In the case of the Smith’s farmland, with the land in trust, if someone were to get injured on the property they could not sue the family directly. Placing land in a trust also establishes a system to keep the land in the family for several generations. Farmland and other types of land holding companies are often placed in trust due to the high value of such land and the way it appreciates over time without incurring federal and state generational estate taxes.

When considering what assets are going to be placed in the trust, families should consider the decisions that will need to be made annually, quarterly, weekly, or even daily to manage those assets. They should think about the kind of alignment that will be necessary between the trustee and the beneficiaries to make decisions about the assets. Certain assets, such as stocks and other financial investments, require different skills and knowledge than others to manage. Trustees can also always hire attorneys, accountants, and financial advisors to help them in their role. It is the trustee’s fiduciary responsibility to be the best steward of the assets held within the trust.

The Where

Most families will choose to create their trust in the state where they live or where their business resides, but some states differ in their tax laws, making certain states more attractive than others when it comes to holding wealth. William did not consider this at the time and held all his assets in trust in California. At the time, this would have been the standard practice. In today’s world, many family business owners want to take advantage of the “tax-friendly” states, namely Nevada, South Dakota, Delaware, and Florida. Conversations about where to hold your family business’s assets are very state-dependent, so you must work with an experienced lawyer and accountant to ensure that the kind of trust that you create is best for your family assets and is also in compliance with federal and state laws.

The How

The actual process of creating a trust is straightforward. The grantor of the trust will reach out to their lawyer and identify which of their assets they would like to place in the trust. The lawyer will then create the legal document, and the grantor will sign over the assets to the trust. A trust does not “come alive” until it owns things. Once it does, those impacted by the trust will begin to act within their roles and carry out the responsibilities outlined in the document.

This is exactly how things proceeded with William and the Smith Family trust. William told his lawyer and accountant that he wanted to place his farmland into a trust. Without much discussion, his lawyers prepared the trust document, retitled the property, and gave the document to William to be signed. The next month, William held a family dinner with his children and their spouses and explained that he had put his land into a trust and that Beth, as the trustee, would now be in charge of decisions regarding the land and farm.

As their father and grantor of the trust, William assured them that Grover and the trust would always take care of the land and them. There were many questions about why Grover could not be the trustee. Once those were answered the family decided that Grover would be “in charge” through instructions to Beth. This allowed the siblings to become comfortable with the change in ownership, but many worried about how this would work in the long run.

The Work Is Done… For Now

In William’s mind, the work is now done. He has spent most of his life growing his family’s business and raising his children to care about it. Using the family trust, William has ensured that the business will not come between his family and that they will always be taken care of by it. With the trust in place, a new status quo has been created within the business. William is no longer “in charge,” but rather the trustee, in this case, Beth, with Grover’s guidance, is in charge. Now, beneficiaries understand that it is on them to communicate with Beth to define what is needed or wanted out of the business. Beth, as the trustee, will strongly consider these requests but will also weigh them against her obligations as a fiduciary of the trust to honor the donor’s intent. This process is the beginning of creating a form of governance inside of the family trust.

However, what no one talked about was the future. Not what happens tomorrow or next year with the trust, but what happens in 20 or 30 years? What will happen when Grover no longer wants to be the trustee advisor? What about when the beneficiaries have kids of their own and want them involved in the business? How will these roles change with future generations?

In part two, we’ll explore how trusts change with time and how families can ensure that their trust stays relevant and beneficial for future generations.

Additional Resources

March 8, 2024