Joan Miller is understandably proud of what she and her siblings have accomplished in growing the small real estate business their parents had worked so hard to establish through grit and sacrifice. Over the past three decades, they have vertically integrated and expanded beyond their parents’ wildest dreams into new states, new property classes and new lines of business (commercial development, construction and solar farms). In addition to this growth in assets and diversification, the Miller family built a strong leadership team and put in place a professional board with independent directors.

Yet, Joan is worried about the future because she and her brothers all struggle to connect their adult kids to the business in any meaningful way. Of the eight in the third generation, six live out of state, most work or study in liberal arts domains rather than business, and two are actively uncomfortable with wealth. Joan and her siblings agree that they want their children to find their own way in the world and recognize that path may not include working in the family enterprise.

Hurdles to Bridging the Gap

Connecting with the next generation is a challenge we often encounter with our families. First, young adults are often busy trying to figure out who they want to be. Wise parents want to give that journey lots of space, as it is important for young people to establish their own identity and sense of purpose in the world, separate from their family of origin. This can be particularly challenging when your family is very successful and has a “big reputation” that can cast a significant shadow.

Second, adults who are early in their career or starting a family truly have limited discretionary time. While attending family meetings may be important to them, they can also resent the demands this puts on their few vacation days. As they start to marry, they will also need to integrate time with their spouses’ families, adding further complexity to calendar coordination.

Third, rising generation family members may not be motivated by passive participation at family meetings largely aimed at educating and updating them. Either because the information is too technical or otherwise overwhelming, or because they dislike being talked at and want a way to be more actively engaged. (“Why do I need to learn all this, it’s not like I have a say…”)

The Miller’s family’s estate planning calls for ownership to be gifted to the G3s over time. Before the G3s have real ownership influence, Joan wants her children and their cousins to understand they are part of a thriving business that brings value to many beyond the Miller family, including their employees, suppliers and customers. Her hope is that they learn to see the business as part of a larger system of opportunity and value which in many ways depends on continuing family ownership.

Connecting to Purpose

At every generation, a family needs to answer the following questions to try to articulate their vision and sense of shared purpose:

- Why do we want to be in business together (benefit of partnership)?

- How are we the best possible owners of these assets (how owners add value)?

- What is the legacy our generation is building for the future (building on prior legacies)?

We find when family members see how they are part of a story that is bigger than themselves they can begin to find meaning in their engagement with the business. Learning that the business generates outcomes that they value (such as high-quality jobs for the community, innovative products or sustainability initiatives) helps diverse family members engage and connect to a shared purpose in the family and business.

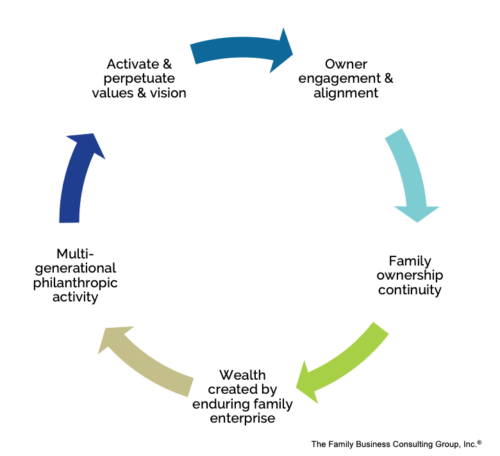

Philanthropy is one activity that often resonates with the next generation of many enterprising families. While family philanthropy can be a source of pride when individuals get updates on the good works of the family and business, we argue that philanthropic families explore actively engaging their next generation in philanthropy as a way of giving them a “seat at the table.” This opportunity will push them to make decisions as a team, teach them to evaluate organizations (including their finances), and allow them to connect the work of the family to values that are meaningful to them as individuals. Multi-generational philanthropic work can lead to a virtuous cycle that sustains a family’s shared purpose, illustrated below.

Leveraging and Amplifying Your Philanthropic Spirit

In our work with families, we have seen many excellent models that nurture the family value of giving back. Here are a few concrete examples you might consider for your family:

- Allocate a pool of funds (typically through a donor-advised fund) for the next generation cohort to give away. With this model, we would suggest the group develop a set of guidelines they can use to select possible grantees, and strongly suggest against any model that would simply allow the group to divide the funds equally, so that each of them is giving the same amount to an organization of their choosing.

A critical benefit of this approach is to have the group work together to align on a few broad categories of giving they can all feel good about, and to navigate the hard choices of comparing all the organizations that each of them would nominate for consideration. In addition, if you establish some clear due diligence criteria to vet possible grantees, this can be a way that family members learn to review basic financials and ask thoughtful questions about organizations – skills that will serve them well as owners in the future. Typically, there is an annual allocation made that the next generation group is responsible for giving away.

Risks to navigate:

- Spend extra time at the outset to clarify the shared giving vision of the group to minimize friction on organizations one family member may want to champion, but others may find controversial. It is important to stress that this vehicle is not meant to replace the giving they may want to do as individuals – but rather it is a tool to help the group learn to work together and find alignment.

- It is important to establish shared expectations of how grant recommendations will be made, how much detail will be provided, etc. The more rigorous the exercise, the more learning that can be gained from the process. However, it could make it harder for folks to fit into their busy lives.

- Inevitably it can feel like a competition between cousins on whose organization(s) will get supported and whose will not. When everyone is aligned on the giving priorities, in most cases, people are excited to learn about new organizations and can generally get to consensus on which group(s) to support. If your family has a history of toxic competition, this may not work for you.

- If you have a formal family foundation, this can be an opportunity to establish committees where the next generation can play an active role in researching grant requests, or work together on a significant grant project (major gift that will allow for some creative input). Leadership at the foundation level offers a prime opportunity for the next generation of family members to gain valuable governance experience, while also collaborating with fellow family trustees.

Risks to navigate:

- Managing a foundation requires more formality and processes than a donor-advised fund. This can be a learning opportunity on governance skills, but important to bear in mind if trying to decide what kind of giving vehicle to establish.

- If the foundation has long-established giving criteria that resonate less with the younger generation, this could set up some tension between generations. It also provides an opportunity to prompt a review of the family’s shared values more broadly. Discuss how might these be interpreted to incorporate the perspective of the younger generation without disregarding the priorities of prior generations.

- To the extent that this forum creates an opportunity for inter-generational collaboration, it is important to ensure that both generations can afford each other’s appropriate respect and work as peers (e.g., if both on Board of Trustees).

- A final model that requires less collaboration can be to provide matching funds to encourage family members to donate from their own pockets. It can be “easy” to give donate money that isn’t really yours, but some families want to encourage family members to develop the habit of giving money they have earned or could otherwise spend. We have observed senior family members offering a 3:1 or even a 9:1 match of the younger generation’s contributions to charitable causes. For instance, in the case of the 9:1 match, it supported a financial gift made by a younger family member who was also serving on the organization’s board. The goal was to encourage family to give of their time and treasure and amplify the younger generation’s impact by multiplying their donation.

Risks to navigate:

- This approach does not naturally lend itself to the collaboration benefits outlined in other two models.

- You may want to coach family members to give to organizations whose missions are deeply meaningful to them — as opposed to giving away money to impress a golf buddy.

Enterprise Evolution and Family Engagement

After talking with a board member who leads his own family’s philanthropic effort, Joan Miller began to see philanthropy as part of the larger evolution of her family’s enterprise. She observed that her conversations about philanthropy sparked interest in the next gens and helped them see the tangible opportunity in connecting with their family enterprise. She asked her brother and his children to attend a conference on family philanthropy in a city where two of his children lived and worked.

One of Joan’s own children served on the board of a small non-profit organization and agreed to share his experience at their next family meeting. With the help of their family business consultant, the Miller family assembled a philanthropy task force that includes members of each generation. They would gather information about family members’ existing charitable activities and gauge interest in structuring a new collaborative effort.

A well-structured philanthropic vehicle can be the most enduring aspect of a family enterprise, perpetuating the family’s values and priorities long past the life of their operating business. As a venue for the leading generation and the youngest to work together outside the business and inside the family, family philanthropy can bolster intergenerational relationships, which in turn sustains ownership continuity for their enterprise.

We value confidentiality. The examples mentioned in this article are composites based on our client experiences.

Additional resources on ownership alignment:

Solving the Puzzle of Ownership Alignment in a Family Enterprise

Developing a Family Enterprise Owner’s Mindset

Putting Ownership Alignment into Practice: The Sanders Family Dilemma

Building a Learning Family: Why Collective Ownership Development Matters

June 23, 2023