Decisions, decisions—how do business families make them? To begin, decisions can be divided into four different categories, each according to the respective roles of an owner; a board member; an employee (or manager); and, finally, a family member in an organized setting such as a family council.

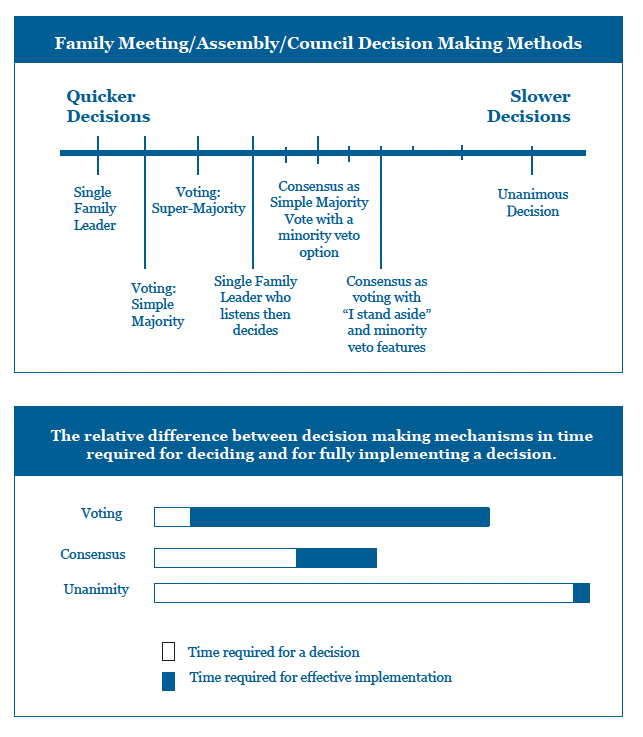

Among owners at stockholder’s meetings, decisions such as electing directors are generally made by casting votes according to one’s ownership percentage, with a simple majority (51% or more) carrying the decision. Boards typically operate with a one-person, one-vote method, regardless of shares owned by the individual directors. A simple majority is usually required for a decision on most board matters, but good family business boards utilize a consensus style, seldom calling for a vote. For management teams, consensus decisions are often utilized to gain broad acceptance and valuable support when it comes time to implement the decision, an important feature when, for example, one department must give up its funding to support another’s strategic initiative. Decision-making authority is often very explicitly defined in business management, so that one knows when s/he can make an independent decision and when, for example, the CEO must involve the board.

As our associates Craig Aronoff and John Ward have written, family business matters on which a family has primary decision responsibility include these:

- Family values/mission/vision

- Communication in the family

- Family education

- Family relations

- Aiding troubled family members

- Resolving family conflicts

- Philanthropy

- Family/business relations

- Family employment policy

- Vacation home economics and use policy

These matters must be decided by families, often in family meetings, family assemblies, or family councils—or their subcommittees. How do families who take on these issues make good decisions?

Centralized Leader

When faced with tough issues, many families default to a senior generation or senior family member. Parents, for example, are the leaders of a first-generation family and have natural decision-making authority. This makes decision making very clear and efficient. Sometimes, in second-generation businesses, the family decision-making authority will reside with an older brother or sister and be passed down to successively younger siblings as an older one relinquishes control of the business voluntarily or for health reasons. Decisions on family matters related to the business may be made by the one who controls the business.

As the family ages and grows, family leaders may respond by allowing family decision making to evolve. Faced with growing interest and pressure for involvement, a leader may opt for an approach that retains centralized decision making (the last word), yet only after checking in and listening to the views of all other family members. Thus, in considering all opinions, the leader’s decision may be regarded as more satisfying to all concerned, even those who might disagree with it. A key factor, of course, is the level of trust and respect commanded by the leader…the more trust and respect, the more others will feel that the decision has been made with consideration of broad input.

While centralized decision making may serve some families, it rarely lasts beyond a generation or two. In many second-generation business families, and even more after the second generation, it is groups that make the decisions. One person making or controlling decisions becomes unfulfilling in that it does not allow all members of the family to feel they have a voice and may even contribute to apathy and reduced commitment to the family business. On the positive side, opening up decision making to a broader group

- makes it more likely that all positions will get a fair hearing;

- helps form the teamwork skills that are required for maintaining unity;

- helps maintain boundaries, in that family members with a voice in family matters will be less likely to inappropriately get involved in management and board decisions; and

- increases the likelihood of all family members feeling that their input is valued and utilized, and potentially solidifies their commitment to the family business.

Voting

Families who make group decisions may adopt a one-person, one-vote rule. As with any decision-making method, voting eligibility must be defined, and it varies by the forum and each family’s own rules for “who will have a voice.” For example, a small family may have a family council that consists of all family members age 16 or older. Some families give the vote only to bloodline family members and exclude spouses, while others include spouses. Larger, extended families may elect representatives to a more formal family council.

It is healthy for families to engage in voting on family matters. Voting can bring decisions to quicker resolution, and as long as everybody understands what the voting rules are, the group generally will be able to support the outcome. Part of the understanding everyone needs in advance is what it takes to decide. A full discussion of all viewpoints followed by a vote with a simple majority rule is a common practice. Families who vote find that they are able to quickly move through material. However, they may not achieve the same buy-in that would be gained by those who seek consensus decisions.

Some families require a supermajority vote (e.g., two-thirds, 70%, or 80%) for key decisions. Their theory is that a simple majority may result in splitting the group in half. They feel more support for the decision after the vote comes only from more agreement at the time of the vote. However, we have seen families who use a simple majority to make decisions work quite well and feel very good about their accomplishments.

Consensus

We know families who have successfully used consensus decision making for years. Consensus offers the opportunity for greater implementation success due to the broad support derived from the way the decision is made. However, some families define consensus as “100% of the group must agree on a decision (unanimity),” and we have seen these families at times struggle greatly as consensus decision making increases real conflict as the group tries to sway outliers to the group decision. Consensus decision making also takes time as a group tries to formulate the questions under consideration so that they may decide as a group. The group can easily wander and frustrate its members unless they have excellent group process and negotiation skills, the assistance of a good facilitator, or both.

Most families realize that unanimity is not realistic and causes too much pain in their families. One person can stop a good decision or frustrate the group to the point where families abandon family meetings. So if it is not unanimity, what is a good definition of consensus that allows forward progress and a fair hearing for minority viewpoints?

One method of defining consensus is a majority vote, with an individual veto feature. This method allows each person to cast a vote in one of four ways. The person can support a decision by voting For it, can oppose a decision by voting Against it, can Abstain from a decision (for example, if the family member feels he or she does not have enough information or that perhaps the decision would in some way benefit him or her and the person wishes to allow the rest of the group to make the call), or can Object to the decision.

If there are only For, Against, or Abstain votes, then the majority will decide, and the family assumes that a consensus decision has been made. This is because an Against vote is understood to convey, “It’s not my first choice, but I can live with it.” However, if there is even one Object vote, the proposal is defeated (no consensus). The reason only one Object vote is needed to defeat the decision is because everyone understands that Object vote to mean, “I cannot live with this decision.” In the case of one or more Objections, some families follow these steps:

1. Modify the proposal right away and vote again. It is important to note that casting an Object vote obliges an individual to lead the process to finding an alternative that can potentially be approved. The individual(s) who objects can explain further the concerns with the proposal, then he or she must offer an alternative (or someone else may, or the entire family group may seek to find an acceptable alternative) that considers all views, and another vote can be taken right away.

2. Discussion and development of an alternative proposal at another date. Discussion takes the form of seeking alternatives and exploring the interests that are being served and not being served by the proposal. Again, the one with the Object vote leads the process. The objection may not be resolved during the current meeting and may continue until the next scheduled meeting or until an agreed-upon deadline. Everyone must agree by the deadline.

- Impasse. If, as a result of an honest effort on the part of all to resolve the impasse, there is no change in positions or acceptable solution found, the objection remains intact and the proposal does not go through.

- Breaking a deadlock. This is not in all policies, yet some families insist on a procedure that keeps them from getting stuck or controlled by an “unreasonable minority.” They may adopt mediation or arbitration procedures, or require a supermajority that includes representatives from all family branches, for example, to move beyond an Objection.

We like this method because it clearly defines consensus, it allows individuals more choices than voting for or against (people are more complex than that, and they want their specific views to be heard by their relatives), and the method does benefit from the efficiencies of voting. Individuals must understand that they should use Object votes only in rare circumstances, and the practices of many families provide evidence that it is very rare that such a vote is cast. Family discussion will flush out early those who would Object, and a consensus alternative is sought rather than taking a decision to a vote too soon. Other variations on the method include the following:

- Requiring a 30-, 60-, or 90-day cooling-off period in order to allow further study and explore an issue or get more data. Sometimes back channels and further research will help all members overcome whatever objection there was to the original proposal or will allow the proposal to be modified so that it will be palatable to all.

- The family may commit to writing the arguments on both sides of the decision and allow a third party (such as a council of advisors or board of directors) to weigh in and render an opinion. This allows an outside group to share their objective feedback as to what they view would be best for the family and business.

- A task force can be assigned to study the issue and attempt to draft a new proposal that will take into consideration the needs of all parties.

Another variation is credited to the Quakers. An individual who originally Objected, after listening to the discussion, may choose to “stand aside.” Standing aside means that an individual is subordinating their interests in favor of the family group’s. An individual is indicating that it is best for the family group to proceed and actively removes oneself from blocking a decision. A decision to “stand aside” can be viewed as an additional kind of vote, short of Objecting, but stronger than an Against vote…and sometimes just the point someone needs to make before allowing the group to come to consensus and move on.

Families have adopted many different procedures for decision making and rather than recommend one for all, we support families coming together and discussing amongst themselves how decisions will be made, in order to adopt a decision-making mechanism. The healthiest situation is one in which the entire family agrees ahead of time, unanimously before a procedure is needed, as to how decisions will be made and then sticks to the decision-making mechanism to which they have agreed.

For an excellent treatment about what arena various types of decisions will fall under in a family business, we recommend you consider reading the book Family Business Governance: Maximizing Family And Business Potential by Craig Aronoff and John Ward,

Family Meeting/Assembly/Council Decision-Making Methods