Like many people, I often start the new year giving a lot of thought to how I can maximize my sense of fulfillment and joy in the coming year. I consider how I can better organize my work, maybe my pantry, and even my leisure travels. Inevitably, I also get to wondering why this kind of intentional planning is not a more frequent or regular practice in my life. To quote the old adage, why does “the urgent get in the way of the important?”

Because the work we do with enterprising families is often centered around helping them focus on important planning for the future, we regularly see how urgent matters can make this longer-term planning difficult to prioritize. One aspect of longer-term continuity planning that is often underdeveloped is the leader’s need to make plans for their own personal continued sense of fulfillment and joy when they are no longer in a daily leadership role in the business. Not only does this absence of planning put these individuals at risk for feeling adrift and unhappy in retirement – their inability to imagine a fulfilling life outside the business may well put the entire succession process in jeopardy.

My recently published book: Transitioning from the Top explores the issues that derail transition planning and shares stories from CEOs who have done it successfully. Below is an abbreviated excerpt from the book that provides the responses of these successful family business leaders to this fundamental question:

Why would healthy, capable and driven people let go of a powerful role they enjoy if they have nothing to move toward afterward?

Successful business leaders understand that significant business changes require planning. But they may fail to recognize that what is true for the enterprise is also true for the individual. Given the increasing number of post-retirement years in developed countries, it is surprising how little planning individuals typically do for this phase of life. For example, a survey of recent retirees found that 62% had retired without any idea of how they would craft a life or adjust to retirement. The trend has prompted experts to point out that many people spend more time planning a wedding than planning for retirement.1

Popular books like Stephen Covey’s excellent The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People encourage us to consider all our roles (e.g., mother, entrepreneur, friend, volunteer) and ensure we are investing time in the important priorities for each.2 But in reality, many of us struggle to apply this practical wisdom consistently. In particular, ambitious and successful people tend to invest a significant percentage of their time and energy in the execution and development of their professional role. This makes us more likely to fall into what I call an “identity trap,” where your career role comes to define too much of your identity, making it difficult to move comfortably into retirement.

If 80% or more of your waking hours are consumed with doing one thing and being one person (the boss, elite athlete, mom), when the time comes for you to relinquish that role in whole or in large part, it may lead to a tremendous sense of emptiness, confusion, or lack of purpose.3 Individuals in this situation may struggle with a sense of not knowing who they are anymore, a disorienting feeling, to say the least.

While the loss of one’s central identity is certainly a major challenge, there are a number of additional, more practical losses that come with the end of the leadership role and may contribute further to the challenge CEOs have with their transition. Specifically, positions of leadership at work often come with perks, authority, privilege, and status that may not be readily available in retirement, representing further costs of movement into the post-work stage. Here are several of the most prominent ones:

Office and administrative support: Typically, CEOs have a nice office arrangement, as well as a capable administrative staff that knows them well, and may have long provided personal administrative help in addition to assisting with CEO/business-specific tasks.

Decision-making authority: When you represent the “here” in the “buck stops here,” the idea that decisions will continue to get made without your input or guidance can be hard to swallow. While a retiring leader may understand rationally that someone else is going to be stepping into that role and making those decisions going forward, grasping that in the abstract and accepting it emotionally can be very different matters.

Access to perks: In addition to an office, meeting space, and administrative support, many CEOs enjoy access to transportation, a large entertainment-expense account, high-end health benefits, and myriad other perks that support their work responsibilities, are considered part of their total compensation, or both.

Loss of status: We tend to be reluctant to admit that high status — as associated with prestige and wealth — is something we actively pursue. But humans are actually wired to seek status as a way of protecting their role in the community; so, it’s more natural than we may realize.4 Moreover, though a retired CEO may still have a great deal more status than the average person, they may experience subtle shifts in their community standing, access to decision-makers, and even ease of making a hard-to-get dinner reservation.

A Few Tips to Consider…

1. Recognize over-commitment to your professional identity: Be aware of the extent to which you are committed to your professional role to the exclusion of the development of other meaningful roles and pursuits.

While working, especially early in your career, it can be difficult to find the bandwidth to engage in much else as you are focused on building your business and your leadership, while perhaps also contributing to raising a family. Even if you recognize such over-commitment, addressing it immediately may not always be practical. So, at the very least find ways to enrich and broaden your professional roles where possible. For example, ensure your leadership gives you a chance to engage in both analytical work and mentorship (at the team or individual level).

2. Develop other interests: While it’s important to have interests outside of work, sometimes you can leverage roles you play through work or family to start with minor extensions of your interests. For example, get involved in leadership for your industry trade association or serve on the board of your kids’ school or a small local nonprofit. Ideally, over time you can broaden your outreach to invest yourself in athletic interests, hobbies, or civic organizations that are fulfilling to you as a person.

It’s important that the interests feel genuine to you. Former U.S. president Jimmy Carter took on many post-work roles, from founding the Carter Center to advance human rights to volunteering with Habitat for Humanity — where he would go out on projects and simply cut siding alongside other volunteers. By all accounts, he embraced each new role, rather than comparing it to what he’d experienced as President.5

3. Take planning seriously: Give real time and thought to how you will fill your days when you are no longer leading the business. “Play golf” is not a sufficient answer, unless you are a passionate golfer with many friends with whom you can share this interest and who can push you to keep growing your skills. The same applies for “I’ll travel,” unless you are determined to see most of the world, have the means to do so, and multiple people with whom you would enjoy traveling.

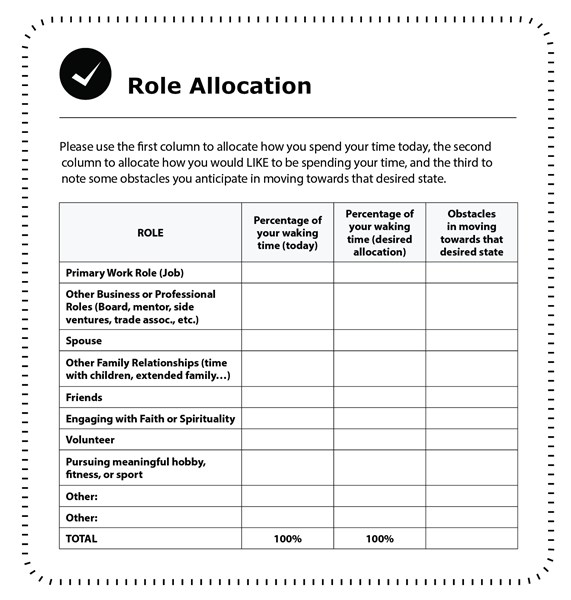

Sit down and think through your daily routine, asking yourself serious questions. What goals will you pursue? How will you pursue them? Who will it involve? Where will you go and how often? How will you feel you are making a meaningful impact and leveraging your knowledge and contacts productively? As Lanse Crane, former CEO of Crane & Company, said, “I knew there are other lives out there.” Think about which of those other lives you most want to pursue in retirement. The exercise below on Role Allocation can help evaluate how you currently allocate your time and how you’d like that mix to look in the future. Make a few notes on what obstacles you face to get from your current state to a desired state of time invested for each of these broad domains.

4. Understand — and plan for — what you’ll lose: As you plan your transition out of leadership, take stock of all the perks and benefits that come with your current role and consider which you need to replace. Bear in mind that this can impact your personal income. For example, if the company has paid your club membership to date, will this continue or do you need to budget for this expense? More challenging for many is losing the administrative support on which they have come to rely. Take honest stock of the personal (not related to business leadership) work your administrative team supports today, and think through how you will get this work done going forward. Do you need to hire a part-time administrative assistant? Where will you house the files you need to access for your board or other professionally related roles?

5. Formalize your role: Give yourself a post-work title. That may sound funny or contrived, but it helps to think through how you want to describe what it is you do now that you are not going to be the CEO or leader of the enterprise. You can make this lighthearted if that is in keeping with your personal style: “Retiree in Training” or “Designated Troublemaker” may go on your business card. I have seen many family leaders modify their business card to say “Shareholder.” A simple adjustment like that can elegantly maintain your affiliation with your family’s business.

6. Practice your pitch: Just as you practiced for countless presentations and speeches as CEO, it can be helpful to practice describing what you do in your post-work life. Ideally, you will have started to envision a role or series of roles for yourself now that you have the new bandwidth to deploy. Think through how you would articulate this to an old friend at a reunion or to a person you meet at a conference. Even a short description, like this one from a former CEO, can do the job: “I currently divide my time between board service for a couple enterprises and an education task force for our Mayor, along with spending quality time with my family and fly fishing whenever I can.”

This article represents only a brief glimpse of the deep insights provided by CEOs who have successfully managed Transitioning from the Top. It is my hope that sharing their stories can foster empathy and understanding about this aspect of the continuity planning process.

As indicated at the open, this book also includes stories, tips, and tools that are intended to provide some ideas and inspiration for this next phase of life – so that family business leaders might approach their post-leadership life with joy and enthusiasm.

[1] As noted in Nancy Schlossberg, Revitalizing Retirement: Reshaping your Identity, Relationships, and Purpose (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, 2009)

[2] Stephen Covey, The Seven Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change (Simon & Schuster, New York, 1989).

[3] For an academic perspective on this issue, see Peter J. Burke and Donald C. Reitzes, “An Identity Theory Approach to Commitment,” Social Psychology Quarterly, Vol. 54, No. 3 (September 1991), pp. 239-251.

[4] See for example David Rock, “SCARF: A Brain-based Model for Collaborating with and Influencing Others,” NeuroLeadership Journal, 2008, Vol. 1, 1-9.

[5] See for example Carter-related anecdotes in Peter Buffett, Life Is What You Make It, Harmony Books, 2010.

Transitioning from the Top: Personal Continuity Planning for the Retiring Family Business Leader

by Stephanie Brun de Pontet

“My goal for this book is to share the compelling stories of retired CEOs’ journeys so that other driven individuals may start to imagine a post-business leadership future that inspires and excites them, even if they are a long way from retirement themselves,” explains Stephanie. “In addition to the real examples, the book offers numerous assessment tools to serve as conversation starters for the leader’s planning efforts.”

The book draws extensively on the experiences of more than a dozen former family business leader interviewees. These highly driven and accomplished business leaders share stories and lessons from their own personal continuity journey as they transitioned from the top of their companies. Combining these anecdotes with knowledge from years of consulting and research, Stephanie helps leaders broaden their sense of self as they look forward to a rich, purpose-filled next chapter in life.

Major ideas and themes covered include:

- How central your professional role is to your overall sense of identity

- How difficult (or easy) it may be for you to make significant changes

- The role of your physical and emotional health and resilience.

- The strength and nature of your key relationships (spouse, children, colleagues, and others)

- The stability and structures of the business (has it evolved adequately, for example, to support the transition?)

- The strength and relevance of your community networks

- How your cultural context might affect the transition

- How to translate your skills, passions, and experience into future opportunities

- The importance of concrete yet flexible planning

- Defining measures of success that you can track

- Understanding and overcoming common roadblocks

198 pages, published by Palgrave Macmillan. Hardcover list price: $34.99 | Ebook: $24.99

January 10, 2018