An active board of directors, either advisory or fiduciary, that includes independent outside directors sets the optimal governance oversight tone in a family business. FBCG studies have shown that the highest-performing family firms tend to have a fiduciary board with the majority of board members as independent outsiders versus family members.

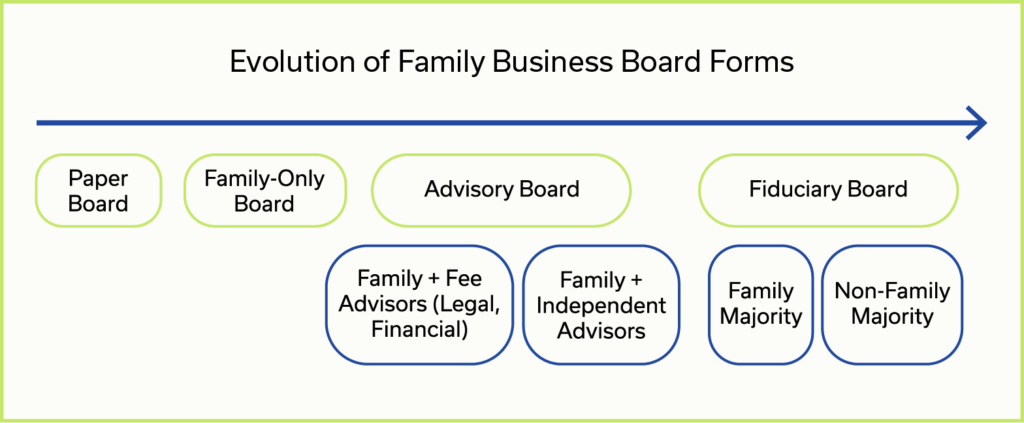

The question, then, is how best to create such a board. The boards of most family businesses that get it right have evolved into an ideal form, rather than starting as one. That is, they transition from a “paper” board — described as one that exists only on paper, including annual minutes and required legal documents — to a family-only board, to an advisory board, to a fiduciary board with family members as the majority, to a fiduciary board with non-family members as the majority (see the figure below). Each stage represents a meaningful change from the previous one.

Family businesses that evolve their board structures to meet the growing needs of the family and business gain greater understanding and appreciation for complexities of the governance process as well as for how best to harness the board with regard to innovation and other key areas. Beyond the board’s form, several other dimensions are important to consider such as size, composition, rotation, retirement and evaluation.

Size and Composition

An FBCG survey of 360 family business boards shows the average size to be six board members, with five to nine as optimal. While data suggest that boards with a majority of non-family board members will increase the probability of greater performance, the key driver of success is a combination of highly qualified family and non-family board members representing complementary experience, skills, and perspective.

Starting with a family-only board, Granger and Associates, a waste and energy company, made steady progress over the first two generations. However, as business demands grew, opportunities became more complex, and capital needs increased, it became clear the family would benefit from outside points of view.

After in-depth education regarding the value of outside directors, one family member agreed to exit the board, recognizing that it was for the collective good of the family and business. Two other family members resigned later as they became believers in the blended family/independents governance model.

Along with enduring some family pain, it took an open mindset to promote the board’s evolution. With regard to governance, some families may have had outside board members for generations, while others are just becoming accustomed to the idea.

To implement, the Grangers used a task force to create an effective blend of family and non-family board members. It used strict qualification criteria including deep experience/knowledge of the solid waste and renewable energy industries to identify independent director candidates. Concurrently, the task force applied a less stringent set of criteria to assess family members. Today the Granger family is happy to have a board with four family members and three outside directors, benefiting from board members’ complementary viewpoints.

Rotation and Retirement

Rotation and replacement of board directors through a combination of term limits and mandated retirement ensures a steady flow of fresh ideas and perspective, preventing the board from becoming stagnant. Additionally, agreed-upon terms of office induce the chair or owning family to review director performance periodically. If there are term limits, the downside is that they may motivate effective directors to leave before management or owners want them to.

The goal in structuring board terms should be to maximize both freshness and stability. On one hand, the board should remain relevant and responsive to the company’s changing needs. On the other hand, board structure should also afford directors an opportunity to gain a long-term perspective on the business and in-depth knowledge of its owners’ values, temperament, and goals.

When the family board members of the Behler Young Company, a Midwestern provider of heating and cooling products and services, heard two longtime independent directors were opting not to renew their terms, they were energized to begin a search process for new members with a “non-status quo” approach to governance. Soon the search landed two directors with fresh and complementary perspectives, as hoped.

Establishing a mandatory retirement age for board members has similar pros and cons. On the plus side, a mandatory retirement age facilitates a graceful transition for more senior board members. On the other hand, because higher age is not synonymous with lower involvement or insight — and may actually relate to deeper knowledge of the company and its industry — forced retirement may result in the loss of highly valuable directors.

An innovative option is to find a supporting role for an aging yet strongly contributing board member. For example, instead of retiring a chairman, that member can be named Chairman Emeritus, acting as a senior ambassador for the company while visiting the business and attending high-profile industry events.

Board Evaluation

A robust board-evaluation process is a must to ensure a well-functioning, active, and involved board. Systematic evaluation uncovers and addresses issues related to board function and individual director contributions. Some families have standardized board evaluation processes, while others take a more casual approach.

Assessment of directors should account for the fact that advisors paid an ongoing fee, such as lawyers and accountants, are not generally considered purely independent board members. The paid advisors earn ongoing service fees, whereas other outside advisors working only on board governance activity should be able to discuss important topics from a fully unbiased position.

Similarly, some family enterprises ask their family business consultants to attend board meetings, allowing them to observe proceedings and provide input — here again, assessment of the consultant’s value is important. Another creative technique to gain expertise is to have an attorney or accountant serve as an officer. Since an officer of the company does not have to be a board member, some family firms have elected an attorney as secretary or an outside accountant as treasurer, again assessing their contributions carefully.

| Confidentiality is important to us. All cases, anecdotes and examples cited by name are publicly available cases or have been approved for use by the family business described. All others are hypotheticals, composites or amalgams based on our client experiences. |

This article is adapted from the book Innovation in the Family Business: Succeeding Through Generations published by Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.