Although family offices are almost always formed for financial and legal reasons, at their heart, they are about family. The family office is designed to serve the family and the family largely determines the culture of the office: the shared attitudes, values, goals and practices of the people who are served by, or who serve in, the family office.

In turn, the culture is significantly a function of the repetitive and predictable patterns of interaction among family members, as well as between family members and the rest of the world. We generally refer to these patterns of interaction as “family dynamics.”

Influences on Family Dynamics and Family Office Culture

Described below are inherent family office characteristics that set a perfect stage for the expression of family dynamics and, hence, for their robust impact on family office culture.

Few Preconditions for Participation

Other than family membership, there are few preconditions for participation in a family office. As a result, investment and operational decisions by some family members and family owners may be derived more from personal opinions and preferences than from education, relevant experience or objectively obtained information. While the absence of preconditions might ensure inclusivity and a high level of family engagement, this could also contribute to tensions between family members who wish more objective decision making and those who believe their opinions alone are sufficient bases for determinations. It is not uncommon for independent directors and family office management to be pulled into this nonproductive dynamic.

Protective Function

Family offices are in their very essence business structures that insulate, protect and shield family members from external circumstances and risk. This shielding can sometimes give the impression to the family that “anything goes.” In this circumstance, it is difficult for other family members or for non-family managers to push back and enforce appropriate limits on behavior or emotional expression. So even if an individual’s behavior is recognized as inappropriate or uninformed, the options for correcting the situation are limited by virtue of the very nature of the family office. In various consulting engagements, I have worked with family members, family office executives or trustees on how to manage this paradox of serving family members while also ensuring that they experience the consequences of their actions.

Authority Vested in Family Owners

As is the case in most family offices, when ultimate authority is vested in family owners and not in business operators, family members may believe that they have rights or authorities which they do not actually have. Such authority entitlement may be compounded by a “bubble of privilege” that insulates family members from experiences that teach humility or empathy for those outside the bubble. Under these circumstances, family members may ignore an established organizational structure and impose their will inappropriately on others. Their interactions with co-owners and non-family managers may be driven by perceptions of authority entitlement and energized by a lack of humility, rather than being based on shared expectations as to governance and management rights.

More than one family office has struggled with developing constructive and acceptable paths to ensure that family members treat non-family managers and staff with an appropriate level of respect for established authority. Take for example, a young man who consistently made excessive demands of the non-family staff. He had grown up in a world of privilege with few limits imposed by parents and projected that lifestyle in his interactions with the family office. Rather than working through the established “rules of engagement,” he would contact staff directly at unpredictable times and demand immediate action on certain requests. When staff hesitated, the man reprimanded them. When confronted on this matter by the family patriarch, he expressed surprise that his excessive requests were considered inappropriate, and that family membership didn’t automatically confer management authority.

Money

Money — how it’s invested, distributed and passed on — is of course a central focus of all family offices. Money can represent and reflect many emotional and psychological meanings in a family: who is loved and how that love is expressed; whether inheritors are viewed as responsible adults or “trust fund babies;” whether there is a sense of gratitude or entitlement; etc. Thus, money and its representations have the potential to inflame or alleviate, accelerate or impede patterns of behavior or emotions in a family, and impact the family office.

In one family, a young adult son was beneficiary of a trust. He was conservative in his spending and participated in various philanthropic activities. He received a modest trust distribution on a regular basis, but special distributions were required for major purchases such as cars or planned vacations. Yet any time he made a request for a distribution, he was met with angry emails and telephone calls from his father (who should not have been involved at all) admonishing him about being a “trust fund baby.” This led to increasing levels of tension in the family and had a disruptive impact on family office executives who needed to deal with a disgruntled wealth creator and dissatisfied beneficiary. What could have been reasonable discussions about parental support and next generation independence turned into highly charged familial conflict.

Closed Systems

In Newton’s first law of motion, an object (or system) will remain stationary or unchanging unless acted upon by an external force. I sometimes use this observation as a metaphor for family offices. Very wealthy families and families of privilege are often isolated merely because of the lifestyles they are able to live. Privacy, confidentiality, concern about being judged by others — all these factors contribute to a sort of “closed system” that is resistant to change because there are few opportunities for “external forces” (e.g., independent advisors, information about other family offices, etc.) to penetrate the boundary around the system. As a result, patterns of family dynamics may persist simply because people don’t know any better. As they say, “A fish doesn’t know it’s in the water until it is out of the water!”

The Impact of Disruptive Family Dynamics

It’s not difficult to appreciate the potential impact on family office culture of the various family dynamics:

- Family members and non-family managers may be distracted, tense or resentful because some owners promote decisions that are not informed by an understanding of best practices.

- Non-family managers and family members may feel depleted by excessive demands or by “out of bounds behavior” and may feel they have few options to manage such behavior.

- An atmosphere of people “walking on eggshells” because what might have been simple and easily managed family decisions become inflamed by what money represents to the parties involved.

In these and other instances in which family dynamics intrude on family office culture, the potential risks are significant:

- Difficulty retaining high-performing management and staff who may seek greener pastures where they would not have to walk on eggshells due to family conflict or tension.

- Difficulty hiring top performing non-family managers who would expect best practices to be implemented by an appropriately informed ownership group.

- Exits by family members/owners who become disheartened by the emotional baggage being carried by the family office.

- Bad examples for members of the rising generation who observe their seniors behaving poorly.

As Matthew Wesley observed in his excellent blog post “Culture Does Indeed Eat Structure for Breakfast,” these risks are likely to occur regardless of how well organized, governed or operated is the family office.

Because the very nature of the family office potentiates the expression of family dynamics, softening their impact is a difficult task. A common response is to attribute problems to individual family members or family subsystems (e.g., couples, nuclear families, married-in, or specific branches), label them with various less-than-complimentary terms (e.g., narcissistic, toxic, dysfunctional, etc.) and consider efforts to change personalities or subsystem behavior.

Under certain circumstances, a focus on individuals or subsystems could be the right approach, but especially when there is severe psychopathology, because those dynamics have an outsize impact on the people and systems around them. However, severe psychopathology in a family is relatively rare and, in case you haven’t noticed, modifying individual adult behavior can be exceedingly difficult!

Furthermore, aside from having questionable efficacy, labeling people and attributing problems to individuals or subsystems runs the risk of polarizing family members and creating “camps” in the family: If one or two family members or subsystems are viewed as responsible for cultural dysfunction, the family runs the risk of fracturing and further intensifying the dysfunction. Applying labels may reflect an effort to locate problems in those specific parties, thereby avoiding the possibility that everyone served by a family office may need to accept some responsibility for change.

Creating Family Alignment with Cultural Enhancement Goals

In my experience, a better approach to disruptive family dynamics is to develop a strategy that seeks family alignment around a set of cultural enhancement goals that ally family members toward the objective of enhancing overall family culture. This is a process that benefits from long-term commitment and is tailored to the specific situation of the family in question. When done well, cultural enhancement itself can become integral to the family culture and be relied upon to manage future challenges. Although this approach should be part of an overall strategy for the family and family office, there are two key components I have observed of successful cultural enhancement strategies for a family office.

1) Consider What Is “Yours, Mine and Ours”

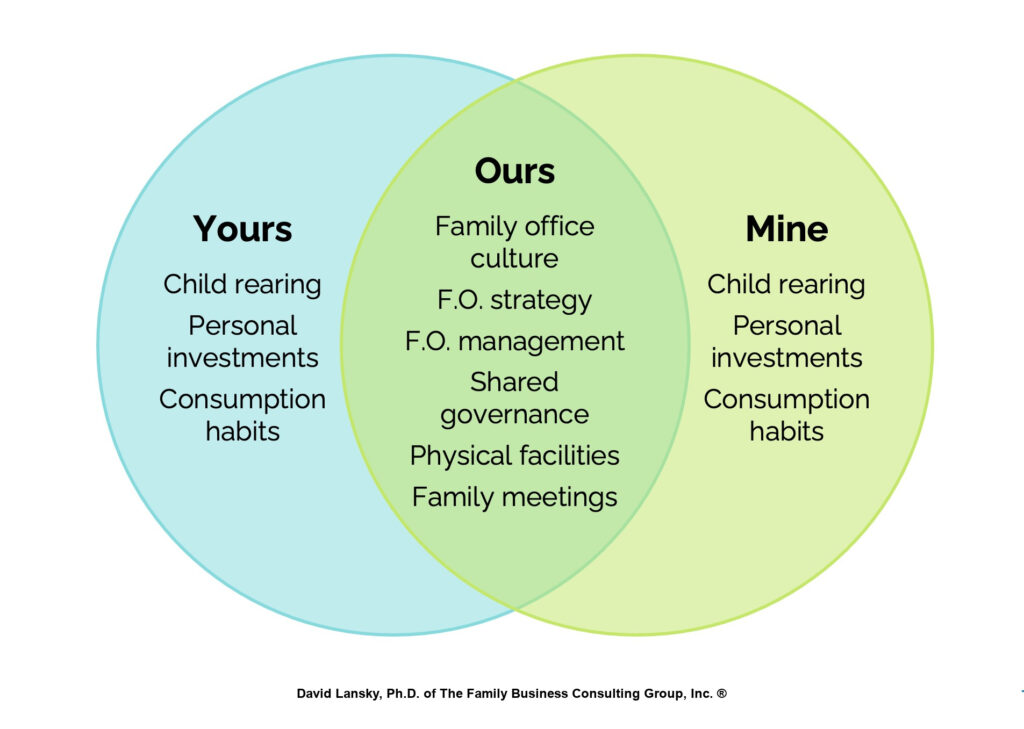

Because, as noted above, ownership of the family office is widely distributed, authority is vested in family members, and participation is based more on family membership than on objective preconditions, it is easy for family members to lose sight of the fact that many elements of the family office are shared by other people. When that perspective is lost or missing, a self-focused orientation may dominate, and this is when family dynamics and personal biases may be most likely to be expressed. Thriving families I have known have recognized their vulnerability to this self-focused perspective and have re-oriented that focus by engaging in discussion and exercises that emphasize the shared nature of the family office.

One simple exercise (illustrated below) is engaging the family in conversation about shared ownership: what is yours, what is mine and what is ours. This discussion can help emphasize the shared nature of various financial and non-financial assets, clarify appropriate and inappropriate behavior in reference to shared assets and encourage a less self-referenced perspective.

2) Externalize Challenges

Another approach to cultural enhancement is to engage family members in discussions that I call “externalizing challenges.” Family dynamics are likely to emerge as disruptive factors when family members believe there are competing interests within the family and/or when internal polarization occurs because individuals or subsystems are identified as “the problem.” Engaging the family in discussions about external challenges is one way to help enhance family alignment. The challenges discussed could be economic, as in: “These are tough times. We need to work together to ensure that economic conditions do not jeopardize our family’s wealth.”

But there are other challenges which might be more meaningfully reconciled through discussion in the long term, for example:

- “Our goal is long-term continuity of the family office and natural forces of geography, family size and diverse values can undermine that goal. How can we pull together?”

- “Family wealth can enhance or undermine lives. How can we ensure that our wealth enhances and does not hurt our family?”

- “Our culture is one of the keys to our success and that culture is hard to maintain in this day and age. How can we win the battle to ensure our culture remains healthy and vital?”

By engaging in a process of externalizing challenges, family members have an opportunity to view themselves as aligned with each other, avoid the polarizing effects of labelling and reduce the impact of disruptive dynamics.

Conclusion

In summary, it is tempting and easy to view disruptive family dynamics as the result of particular individuals or subsystems within a family. However, it’s important to understand that the nature of the family office itself gives rise to some of these disruptive dynamics. It’s equally important to understand that family office culture can be impaired and undermined by these dynamics and by efforts to locate problems in individuals or subsystems.

The best approach is to take steps to align the family toward a unified strategy to enhance culture for the benefit of all.

September 19, 2022